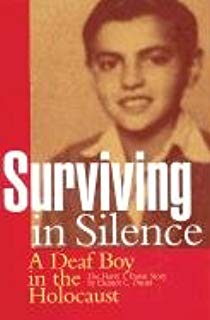

Surviving in Silence: A Deaf Boy in the Holocaust, The Harry I. Dunai Story

Hardcover – Jul 26 2002

by Eleanor C. Dunai (Author), Harry I. Dunai (Author), John S. Schuchman (Foreword)

Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press, 2002. 184 pages. $29.95, hardcover 1-56368-119-6.

Reviewed by R. Dan Schlossberg, Independent Scholar

Surviving in Silence is a biographical description of the memoirs of a deaf Jewish survivor of the Holocaust. Harry Dunai was born in Czechoslovakia in 1934, and until the age of six, grew up in the company of his large family of twelve, who lived a hard-working yet pastoral life in a small village in the Carpathian Mountains.

In 1940, Harry was enrolled by his mother at a deaf school for Jewish boys and girls in Budapest, Hungary. This was one out of four Jewish deaf schools in Europe at that time, and one out of 16 boarding schools for the deaf operating in Hungary at the beginning of the 20th century. Because the school principal instructed her to do so, Harry’s mother left him there without informing him of her departure. This was the first shocking event in a chain of highly distressing episodes that would accompany Harry until the end of the Holocaust. After collecting himself, he became a very good student at the deaf school that taught the oral method (several pages are dedicated to Harry’s study of oral language) and lip reading in class. He learned sign language in between classes among his deaf signing friends.

The year 1944 was the most calamitous for the Jews of Hungary. More than 400,000 were deported to their deaths. The institute was closed down and many children were sent home (or worse). Harry, because he was poor and the fate of his family unknown, was sent to an orphanage of mostly hearing children. The orphanage took a direct hit in the bombings and now the orphans were truly homeless. Children walked through the streets, saying: “Who will adopt me?” Harry’s former and beloved teacher at the institute adopted him for several months. When it became too dangerous to put him up at her house, she dropped him off at the Red Cross camp in Pest where the Arrow Cross (the Nazi collaborator Hungarian fascist movement) was not allowed entry. However, after the fascists took over the Hungarian government and the camp was bombed, the Arrow Cross raided the camp looking for Jewish partisans. Those who survived the raid (one deaf child, for example, simply could not hear the warning of the Arrow Cross and was shot dead) and deportation were put in a ghetto with no facilities where people died from cold, sickness and starvation.

On January 18th, 1945, when Harry was 11 years old, the Russians liberated the ghetto. The boy was told of the death of his parents and two of his brothers. Struggling with his loss as well as other issues related to family, ideology and religion (he would more or less reject Judaism due to his disillusionment), he continued his education at the now Communist government-sponsored deaf school until the age of 16, when he was accepted for apprenticeship at a mechanics company. In January, 1957, a month after the suppression of the Hungarian revolt against Russian Communism, he left for Sweden where he had family and found work. After two years in Sweden, he traveled to London, Paris, Rome, Vienna and Tel Aviv. From Israel, he immigrated to the United States and settled down to work in Los Angeles, where he also had family. About a year later (1960), his deaf sweetheart from London joined him and they married and raised a family of three girls there. The eldest daughter wrote this book from her father’s perspective in the first person based on the telling of his memoirs.

Harry Dunai’s grasp of several oral languages and signing methods of communication facilitated his connections with the speaking and hearing world and formed the base for key relationships with deaf peers, respectively. His own savvy, the network he developed of friends and family and Holocaust survivors, together with the individual and institutional support he intermittently received, were principal factors of his survival during the Holocaust and post-Holocaust period of recovery and renewal.

Mention should also be made of the “deaf club” institution because of its significant role for Harry, an orphan in post-Holocaust Europe. Harry says: “In essence, the deaf club was really my home and a major part of my life where I would participate in sports and daily social activities. It was the positive aspect of my existence” (p. 104). He became increasingly involved at a Budapest deaf club in the 1950s. At this establishment, he made connections and friends and built up his self-assurance, for example, by cultivating his talent for chess. In all the major cities where he lived or visited throughout his life, it seems he could count on the local deaf club to find a haven and opportunity for social connections with the local or wider deaf community.

Surviving in Silence is more a biography than a novel. It is not an elaborate sociological, pedagogical or ethnographic document. The first part of the book, including the Holocaust period, is intense and evocative, whereas the second, post-1945 half of the book more often reads like a chronicle of events. In all, it is a significant documentation of how a deaf Jew, with resourcefulness, excellent learning skills and other qualities, endured the Holocaust and was ultimately able to establish a satisfying life and family.

Source: dsq-sds.org/article/view/557/734