The Jewish Home

December 20, 2018

“Besser, I have a scoop for you.”

The caller was a leading rosh yeshiva – not the type who shares scoops or calls writers.

Rav Elya Brudny had been at a wedding, and the mesader kiddushin had been an out-of-town rosh yeshiva, a tall, distinguished looking man.

He walked up to the chuppah, and took his place behind the microphone: when he said the brachos, it was immediately obvious that he had trouble articulating his words, and it seemed somewhat garbled.

“But then I saw him by the dancing, leading a chasunah, his talmidim around him,” Rav Elya continued, “and I realized that he was getting through to his talmidim better than many of us.”

It sounded dreamy — the plot of kid’s book or maybe an Abie Rotenberg song — a sweet tale of a rosh yeshivah who doesn’t hear and his devoted talmidim.

But this is the real world, where things aren’t so sweet and neatly packaged.

And so I flew down to Toronto to see. You know how people say “no words”? Like, when they want to convey their astonishment speechlessness becomes a way of expressing an awe that words would only limit? In a humble trailer just west of Bathurst Street, I found a world where that awe never fades. No words.

Back when Brownsville was the place, when pushcart peddlers along Pitkin Avenue haggled with customers in Yiddish, the Brooklyn neighborhood had a real rebbe.

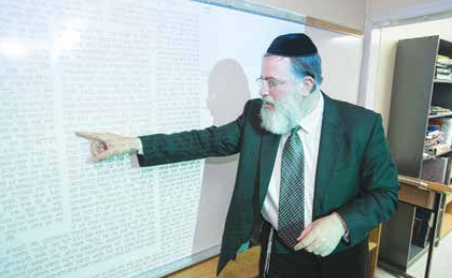

Photo: Moshe, a talmid in the yeshiva, getting Gemara instruction from his rebbe

The Brownsviller-Mezhibuzuh Rebbe, Rav Shmuel Avrohom Rabinowitz, was a son of Rav Elizer Chaim of Yampola, a grandson of the rebbe of Ropshitz. He was reputed to be a ba’al mofeis, a healer, a writer of kabbalistic amulets. His son, Rav Dovid Eliezer, was born in 1917 – deaf.

Rebbes work with words: a child deprived of words, the building blocks of connection, the invisible ropes with which to draw others close, has no future working with people.

He can be a craftsman, perhaps or even a successful peddler, but not a rabbi.

Right?

No, not really.

Rabbi Dovid Elizer Rabinowitz would become an effective and respected shul rabbi, leading a community of deaf and hard-of-hearing Jews in Brooklyn: he taught many lessons, but perhaps the greatest lesson of all was about perseverance.

Photo: Yechiel, who is engaged to be married, returns for a visit to yeshiva

His young grandson, Chaim Tzvi Kakon, was also born with hearing challenges – and with that very same determination.

The Kakon family lived in Denver, and then in Detroit. The zaide, Rav Dovid Elizer, moved away from Brooklyn twice, following his grandchildren so that he could be near them, part of their lives.

Many things were confusing to the child. Days were spent in public school, where he mastered sign language as part of his total communication education, while nights were filled with dreams of learning Torah.

Tough as it was, he came home to his parents, to love and warmth and encouragement, each evening. But then he wanted to go to summer camp.

Tough as it was, he came home to his parents, to love and warmth and encouragement, each evening. But then he wanted to go to summer camp.

Photo: Yehuda, an Israeli talmid at Nefesh Dovid, in discussion with one of the Rebbeim, Rabbi D. Friedman

Young Chaim Tzvi Kakon joined hundreds of other boys in the Mogen Av shul on the first day of camp as head counselors called out names, assigning a bunk to each camper – but he couldn’t hear. He sat on the bench with no clue where he belonged.

In his seforim-lined study, the rosh yeshiva of Nefesh Dovid looks like he’s sharing a routine childhood memory, but when he reaches that recollection, the first day in campus, there is an unmistakable flash of pain. “It was very bewildering. I had no idea where to go, didn’t know who my counselor was or who was in my bunk.”

On a bench near Chaim Tzvi on that summer day sat eleven-year-old Normie Lowenthal. Today, a respected social worker at Baltimore’s Talmudical Academy, Rabbi Lowenthal remembers the moment well. “It’s important to appreciate what Mogen Av was doing. Way before other camps followed suit, Camp Mogen Av was accepting boys with disabilities and special needs, mainstreaming them before it was even a term.”

On a bench near Chaim Tzvi on that summer day sat eleven-year-old Normie Lowenthal. Today, a respected social worker at Baltimore’s Talmudical Academy, Rabbi Lowenthal remembers the moment well. “It’s important to appreciate what Mogen Av was doing. Way before other camps followed suit, Camp Mogen Av was accepting boys with disabilities and special needs, mainstreaming them before it was even a term.”

Photo: One of the ingenious methods utilized by Rabbi Kakon to optimize the astonishing success in the Gemara skills of the talmidim

At camp the previous summer, young Normie had made friends with a boy who did not hear: the boy taught Normie the basics of sign language as a means of communication. “So when I saw Chaim Tzvi looking bewildered and alone, I recognized that he had a hearing impairment, and I was confident I could communicate with him. I introduced myself and we became friends.”

That act of kindness welcomed Chaim Tzvi to the camp experience. The painful start gave way to a spectacular few weeks: while the boys around him were celebrating home runs, Chaim Tzvi was breaking his own barriers. A walk with a friend. A meal at which he’d been attuned enough to pass the milk to a bunkmate. The happy exhaustion at the end of a hike, flopping on the grass, feeling connected by a current of shared satisfaction with others.

The gifts he’d discovered in camp came in handy in school, and that summer reinforced his willpower to keep trying. The evening learning sessions allowed his dreams to expand, visions wide as the grassy lawns in camp: finally, at the age of sixteen, he articulated that secret hope.

His father, Rav Yosef, is a talmid of Rav Moshe Schneider and Rav Aaron Kotler, an accomplished talmid chacham: all the teenager wanted was to go to a real yeshiva and learn Torah like his father. His parents were ready to let him try, but where would a bochur who couldn’t hear feel welcome?

Photo: An elective photography course with teacher, Rick Barrow, who also cannot hear a talmid of Nefesh Dovid davening in the Yeshiva Gedola of Toronto, where Nefesh Dovid is situated

A friend, Yossi Bienenstock, was learning in Toronto’s Ner Israel, and he suggested that Chaim Tzvi join him.

Weak in learning, with no experience in serious yeshiva-style study, the bochur arrived for his bechina with little other than the fire in his eyes.

The rosh yeshiva saw nothing else.

“At the shiva for my rosh yeshiva, Rav Naftali Friedler, I learned what really happened that day,” says Rabbi Kakon. “I came and begged to be accepted, but I wasn’t on the level: when I left the office, some of the hanhala members expressed the opinion that, ‘he is a really nice boy, but…’ The rosh yeshiva banged on the table and said, “I’m not asking you. I’m telling you that we’re taking this bochur!”

(Years later, Rav Chaim Tzvi and Rebbetzin Libbi Kakon would be blessed with a son: the child would be named Naftoli, for the rosh yeshiva who’d welcomed his father to the halls of Torah.)

In Ner Israel, Chaim Tzvi Kakon made two discoveries that would make a big difference to his future. “I learned that a yeshiva is a magical lace; it’s not just about the learning and growth, but about being part of something, the friendships and connection.”

And he learned that Toronto is a wonderful community. “I’d never been there before, but I felt at home.”

Photo: A talmid of Nefesh Dovid davening in the Yeshiva Gedola of Toronto, where Nefesh Dovid is situated

In Ner Israel, the new bochur was placed in ninth grade, with boys several years his junior. “I didn’t care,” he says emphatically, “it was fine. I wanted to learn. I didn’t see the ages of the boys around me, didn’t let it affect my excitement at learning.”

Rebbetzin Libbi Kakon, who has been listening to this account, interjects, “That’s so typical,” she says, “nothing bothers my husband.”

“Not true,” he shoots back.

In Ner Israel, with the help of devoted friends, Chaim Tzvi became a yeshiva bochur: the deafness was no longer the story, because there was a Tosfos and a Rashba and a K’tzos to worry about.

Those glorious years in Toronto came to an end when it became evident that Chaim Tzvi needed to move on. Toronto friends Dov and Nancy Friedberg sent him to join their sons, who were learning in Baltimore’s Ner Israel.

And once again, he felt overwhelmed. “It was a much bigger yeshivah than Toronto, with so many new faces, so much going on.”

He was sitting on a bench on that first night when a familiar face appeared in his line of vision.

Photo: Rabbi Chaim Tzvi Kakon with Rabbi Chaim Mendel Brodsky, rosh yeshiva of Yeshiva Gedolah of Toronto, which has welcomed Nefesh Dovid for so many years

Just as he had a decade earlier, in Camp Mogen Av, Normie Lowenthal welcomed his friend to this dizzying new world.

Rav Shragi Neuberger, the new talmid’s maggid shiur, remembers that first zman. “He couldn’t hear, but that was just a detail, it didn’t define him. What made him unique was his kishron, what made him unique was his desire to learn, and what made him unique was his ability to understand other people.”

The boy who couldn’t hear somehow heard the needs of everyone else, becoming a star. “He was popular, not because he was different, but because he has this special chein, the smile and warmth,” recalls a Ner Israel talmid. So popular, in fact, that the other bochurim voluntarily learned sign language so that they could communicate with him, be in his circle as well.

Another of the heroes that would appear along the journey was Dr. Leonard Siger, a professor at Gallaudet University for deaf students. Dr. Siger had learned in yeshiva but then drifted away from Orthodox life. The brilliant professor knew sign language, and since retirement, he’d been interpreting Rabbi Yissocher Frand’s Thursday night shiur for others in the community. Someone suggested that Chaim Tzvi ask Dr. Siger to come to yeshiva to help him learn Torah.

Chaim Tzvi summoned up the courage to approach this brilliant, irascible, ponytailed academic and ask. “Of course,” Dr. Siger answered. “I was waiting for you to ask.”

The professor didn’t drive, so he would walk two hours each day to give over the shiur: it was he who opened the gates of real comprehension in learning to the determined talmid, exposing the full flavor and depth of the shiur. In time, Chaim Tzvi and the professor became chavrusos for the early morning daf yomi shiur as well.

They would review the shiur each evening. Soon enough, Dr. Siger shed the ponytail and became a complete ba’al teshuva: when he passed away two years ago, it was Rav Chaim Tzvi Kakon and his talmidim who came in from Toronto to perform the levaya and kevura, a final gesture of friendship from a grateful chavrusa.

Eventually, it was time for the tall, handsome yeshiva bochur to find a shidduch.

Libbi Spitzer did not hear well and, like him, was unconstrained by expectations and perceptions. Able to speak, she was a successful teacher at a school for special needs children at the time the shidduch was suggested.

“My husband,” she says with a smile, “makes goals for himself and then ticks them off, one by one. He decided we were getting married, and I was just another box to check off.”

(The rosh yeshiva is beaming as she says this, nodding as if he still can’t get over his good fortune.)

Rebbetzin Kakon continues the story. “I was a Hungarian girl, I knew what I wanted. He told me he planned to become a lawyer, and he would buy me a house and a car.”

The chasunah in the winter of 1989 was joyous – a popular chassan, a popular kallah, beloved families: but in the festival dancing, there was a sense that two worlds were merging, two young people burning with purpose coming together to create something new.

They also knew, this young couple, exactly what it was they wanted to do.

Over the first few years of their marriage, Libbi continued teaching while Chaim Tzvi learned in kollel, eventually earning semicha: in the summers, they allowed their dreams to flourish. Chaim’s Tzvi’s rabbeim at Ner Israel allowed him space on the yeshiva’s campus to host a summer program called Gesher L’chaim, a sort of yeshivah camp for deaf boys. Reb Chaim Tzvi also used the time to earn a master’s in Social Work and he took a position as a therapist at a psychiatric impatient unit, also sitting on the State of Maryland’s mental health board.

And the zaide, who’d moved to Denver and then to Detroit to mentor his grandson, moved yet again: he and his rebbetzin moved to Baltimore, into the house across the street from the young Kakon family.

Seven years of those summer programs created an informal chaburah, a wide group of hearing-challenged talmidim who felt close to this dynamic couple: in 2001, the yeshiva was founded in Toronto.

Neither of them were locals, but the Canadian city had a certain appeal.

“Rabbi Nafatgali Neuberger thought it was a good idea, and he always saw further than most people,” Rabbi Kakon recalls. “I had close friends there from my years in yeshiva, and my wife had family there, but it was my grandfather who really pushed us. The yeshiva was a realization of this dream – and he felt Toronto was the right place for it.”

Photo: Rabbi Kakon learning with a talmid who is also his son-in-law

Rav Yaakov Moshe Kulefsky also encouraged the reluctant rebbetzin, assuring her it was the right path, and Rav Menachem Goldberger told them of the great things accomplished by those who find the strength to follow their destiny.

With these brachos and words of chizuk, the young couple took their young children and their dreams and moved to Toronto.

There, the rosh yeshiva worked with a passionate partner, Dr. Hartley Bressler, a prominent physician who has been deaf since birth: like Rabbi Kakon, he’s been proving people wrong since childhood. Dr. Bressler had previously invited Reb Chaim Tzvi to Toronto to join a Shabbaton for deaf participants. At the time, he introduced the Kakons to Mr. Joe Berman, a local philanthropist who provided the seed money for the yeshiva’s establishment. Rabbi Kakon and Dr. Bressler, two people who never heard of the pessimism, linked arms and established Yeshiva Nefresh Dovid.

“The name is based on a pasuk in Tehillim, 56: ‘Ki hitzalta nafshi mimaves, You saved my soul from death, even my feet from stumbling to walk before Hashem in the light of life.’

“This is what a person with hearing loss feels,” the rosh yeshiva explains, “when he is alone, he is isolated, cut off from what’s going on around him. When a person doesn’t feel part of something larger, he doesn’t feel alive: so through the yeshiva and the network, a young man comes alive, experiencing the light of life.”

Rather than try to describe what makes it special, the rosh yeshiva invites me to join him on a surprise visit to the yeshiva: it’s afternoon, general studies time.

I already know not to expect a massive building – after all, these are the people of substance, not style, the ones who’ve transcended externals rather than getting trapped but still…

It’s a trailer, really, a small structure in a parking lot.

“But look where we are, who our neighbor is,” the rosh yeshiva proudly indicates the impressive building next door.

Yeshiva Gedola Zichron Shmayahu, the community’s flagship yeshiva, saw the opportunity early on. “We could never have opened our yeshiva if not for them,” Reb Chaim Tzvi says, “they made it possible.”

Rav Chaim Mendel Brodsky, the rosh yeshiva of Zichron Shmayahu, welcomed Nefesh Dovid to his grounds – opening up the dining room, gym, and beis medrash to its talmidim. “We eat with them, daven with them, and in general, their bochurim make sure to make our talmidim feel welcome,” says Rabbi Kakon. “They make it possible.”

It doesn’t surprise me that the yeshiva in the trailer feels just like a real yeshiva: the jackets strewn over chairs, the smell of black binding tapes on Gemaros, the delighted laugh of the bochur who’d been swinging from a coatrack as the rosh yeshiva suddenly comes in.

The rosh yeshiva introduces me to the secular studies teacher, an affable Ontarian who teaches math in sign language. “I’ve done this for years, but these are the first group of yeshiva boys,” he says.

I ask him what sets them apart, and he doesn’t hesitate. “Their optimism: they want to do it all and believe that they can.”

The bochurim themselves are a charming group, a young man from the hot, dusty streets of Bnei Brak – his father still learns in Ponevezh – and a Chabad chassid from Europe sit near me. (Although there are different forms of sign language in different countries, the rosh yeshiva and most talmidim are fluent in all of them and are able to easily communicate with each other.)

Some of the boys can’t hear at all: many have cochlear implants and speak flawlessly – but they are all tuned in. The rosh yeshiva insists that I speak to the talmidim. A confident young man takes his place at my side and interprets for those who need, moving his hands in concert with my words.

I tell the boys that Rav Shlomo Friefeld, zt’l, would say that just as we believe that the match between man and woman is divine, the “shidduch” between rebbi and talmid is equally divine: it takes real siyata dishmaya for it to work. The boys smile and nod. Don’t they know it.

After, they gather around the table and field my questions. I ask an Israeli bochur what it is they do differently in Nefesh Dovid, why he feels like his life started the day he arrived – his words – and he looks at the others, as if for encouragement.

Finally, he tells me that as a child he spent many hours out of school, trapped in a world of his own: he passed the time by playing soccer and became quite good at it. He makes an imaginary kick right there, in the beis medrash.

Rabbi Kakon found out about the soccer thing. He called different baale batim in Toronto and learned that there was a soccer league: not everyone was thrilled about admitting a fifteen-year-old boy, but, as the rebbetzin says, when the rosh yeshiva wants something…

“That is different. No other rebbi ever thought to do that for me. I play soccer and it feels so good, it spills over into everything else,” the young man says.

When Gemara is taught in yeshiva, I learn, the words are shown on the screen so the boys all see the daf. “And even while there’ debate whether it’s better or not to teach in sign language,” the rosh yeshiva says, “for Gemara it’s certainly better because it becomes visual, you see the concepts. The machlokes is set up on the screen, Abaye here, and Rava there. The talmidim follow along and really get it.”

He shares a personal tidbit. Sometimes the rosh yeshiva goes to a shiur, and his own friend and personal interpreter Dr. Mitchell Sutton comes along to translate what the emaggid shiur is saying. “And inevitably, other people thank me after, telling me that the presence of the interpreter – the gestures and signs – made it easier for them to follow along too. It’s easier to absorb information when you see it.”

In chinuch, the most important thing is to be attuned, a rebbi has to hear a talmid, what he’s saying, what he’s not saying,” reflects Rav Shragi Neuberger, the rosh yeshiva’s rebbi. “Rav Chaim Tzvi is unique in his koach hashmia, he picks up nuances. It’s a mix of really caring about talmidim and being very sharp. He’s a natural mechanech.”

But talmidim agree that it’s the rebbetzin who gives the yeshiva its heart. Along with creating the home that’s as much a part of the yeshiva as the dormitory, she will often reassure worried mothers that their sons will flourish in the yeshiva. At the request of the yeshiva’s board of directors, she handles all the fundraising. “My husband is simply too busy with his boys, he wakes them up in the morning and is with them all day, Shabbos too. That’s his mission, and this is mine,” she smiles.

The Kakon family has embraced their role as well. “The bochurim come over Friday night after the seudah,” the rebbetzin says. Two of the Kakon daughters, who do not hear, married talmidim of their father’s yeshiva.

The rebbetzin serves as a surrogate mother to many of the foreign bochurim and is a respected teacher in the local Basis Yaakov as well. She is also unafraid to be honest: it’s her willingness to share her own struggles that makes her call to be strong so much more effective.

The Kakons have several children – two with hearing loss, some who hear perfectly. And then, just around the time Nefesh Dovid was born, they were blessed with a little baby girl, Devoiri.

The rebbetzin’s face visibly lights up when she mentions the name.

But, as she often concedes in her popular lectures, it wasn’t always easy.

Devoiri was born with Down syndrome and was later diagnosed with autism as well.

Those first few months were very difficult: there were older children; there was a yeshiva… and then Devoiri.

In a written tribute to the family’s rav, Rav Menachem Adler, the rebbetzin – a gifted writer – recalls: I remember when we were poor and downtrodden. What to do? Where to go? The Rav turned his kind eyes to us and helped us rebuild. He believed in us. He believed in our children and he believed in our future when we could not see past the day.

When our severely disabled daughter was born adding more weight to my heart, the elderly Rav shuffled his way down the street to our Shabbos table week after week, 52 consecutive weeks, on the way home from Friday night prayers. He gazed at the candles that were so hard for me to light, gazed at our table that almost did not get set, gazed at our family that almost did not grow to be strong and capable.

Then he turned around and left, slowly heading on to his own home and his own table where his Rebbetzin waited, unbending and loyal. His children did not know until I told them. He is the unknown, the status of the true faithful.

Is this what G-d does? Visit us week after week, moment after moment? Does he wait and watch and we do not turn to see Him?

In the early months of Devoiri’s life, the rebbetzin – undaunted for so long, rising above her own challenges to teach, marry, mother and build a yeshiva – felt like she would give up.

“The rosh yeshiva reminded me, he encouraged me, he inspired me. He lifted me. And he waited for me,” she recalls.

The rebbetzin mentions another of those figures, Divine messengers to offer encouragement or assistance at the right time. “My great-uncle, Rav Avrohom Chaim Spitzer, the old Vienner dayan, was a big part of our lives. I grew up revering him, we knew he was a tremendous talmid chacham, but he was so approachable, so easy to connect with. After Devoiri was born, he sent me a message, along with the funds: I was to get more household help, he paskened. He became a big part of the yeshiva too, and many of my husband’s talmidim would go to him for bracohos.”

Family, faith, patience – and a sense of humor.

One day during Devoiri’s first few months, Rav Chaim Tzvi welcomed a visitor to his home: Dr. Leonard Siger, his old chavrusa from Baltimore. The rosh yeshiva was hilding the newborn infant when he opened the door, and he informed the guest that the baby was born with Down syndrome.

“Okay,” the professor didn’t miss a beat as he looked at his old friend, “but you know that everyone has some sort of challenge in life, don’t you?”

“It’s true at home and it’s true in yeshiva,” the rebbetzin remarks. “My husband teaches the boys to laugh, to accept themselves for who they are. Go live. There’s too much beauty and meaning to get stuck on the things that don’t work. People from other yeshivos see our boys in the street, or at weddings, and they wonder why they seem so much more alive than boys who can hear perfectly!”

To live in the light of life…

In her inimitable style, the rebbetzin writes:

The boy, Shmili, who comes in sad. His eyes. I cannot look at his eyes. I see him Friday night. I say to him, something happened to you. You look different. One week you have been here. You look different.

He smiles slightly. The first hint of a smile.

He quips, I must have grown taller. Oh my. Don’t we have a sense of humor?

He did grow taller.

Eitan.

His eyes. Dark. They brighten noticeably week by week. Dark like a night sky, not the dark of tar on the ground.

Kindness. Acceptance. Letting dreams free.

Yisroel Avraham.

I am not going to Toronto to a “DEAFO YESHIVA”! He yells. I am not DEAF – I am fine! Everyone can go fly a kite. His parents drag him to Toronto.

I am not going home! I want to stay here at Nefesh Dovid. Forever.

My husband drags him to the airport after reassuring him he will be back in two weeks to continue watering his dreams. He is coming back not to a deaf yeshiva but a yeshiva for those with hearing loss.

They all come back.

So many of the lessons we preach, what we expect from our children, are relevant to all parents, not just in the special needs community,” the rebbetzin says. We are back at her home, where the dining room table is elegantly set. (Remember, I’m an old Williamsburg girl, she laughs, and she insists I accept a slice of cake.)

“The rosh yeshiva always tells the boys that they’re not nebach cases, that rachmanus has its time and place.”

There was a bochur who had trouble speaking clearly: years of hard work and therapy paid off, and he developed the ability to articulate himself. Not long after he received the gift, he spoke with chutzpah to his rebbi.

“On one hand, it was a great simcha to hear him speak so fluently,” the rosh yeshiva recalls, “but at the same time, I realized I would be doing him a disservice if I wouldn’t point out that he’d behaved improperly. “I’m so happy you speak so clearly,” I told him, “but there are also expectations about what you can say and what you can’t say,” he chided.

I tell the rebbetzin that one of the boys in the yeshiva, learning that I worked for a magazine, urged me not to write about the yeshiva. “Then everyone will come, not just boys who can’t hear, and we don’t have room for all of them,” he said.

The rosh yeshiva and rebbetzin laugh. The rosh yeshiva jokingly puts a finger to his lips, as if charging me to keep his secret.

“Who doesn’t need someone to believe in them?” the rebbetzin asks. “So many boys come here dying inside and waiting for someone to tell them it’s okay; they can fly as high as they want to. That’s what we do.

“Parents don’t mean to limit their children, they just worry too much about reputation, so they try to conform without giving the child enough space to be himself. And then there are others, parents so scared of disappointment that they discourage them from trying. It’s easier not to try than to fail, they think, but it’s not true.”

She shakes her head. “It’s better to fail, though. You know why?”

“Because,” Rebbetzin Kakon, wife of the rosh yeshiva of Nefesh Dovid, speaks softly, “because then you tasted the joy of trying, and once you’ve worked hard, you’ll do it again.”

This article and accompanying photos were originally printed in Mishpacha Magazine.

Source: The Jewish Home